From Townsend’s big-eared bat pups venturing out on their own, to sand dollar babies free-floating in the ocean, there’s so much happening at the Seashore this August. Read on the learn about these marvels…and go out to experience even more of Point Reyes’ August delights for yourself!

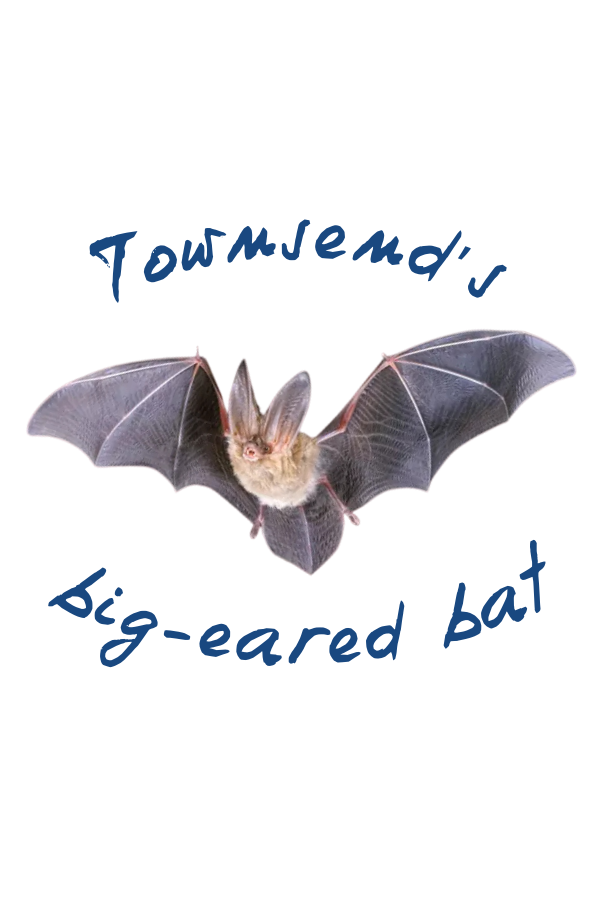

Townsend’s big-eared bats

This month, send your best wishes to Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) pups, who are courageously beginning to leave the safety of their roosts. The young bats were born blind and grew up in the warmth and safety of maternity roosts in the Seashore, forming close bonds with their mothers (and squawking when their mothers were away). Within three weeks of being born, the young bats are able to fly; after two months, many of the newly-independent pups venture out on their own. By August, the maternity group begins to disperse, marking an end to the breeding season.

Townsend’s big-eared bats are listed as a Species of Special Concern and a Species of Greatest Conservation Need due to destruction and disturbance of their maternity sites. There are concerns that the bats’ nesting sites—abandoned mines and buildings, for example—will continue to decrease in number as they collapse or are repurposed.

Keep an eye out for bats around sunset as they begin their night-time foraging foray. Thirteen species of bats have been reported at Point Reyes.

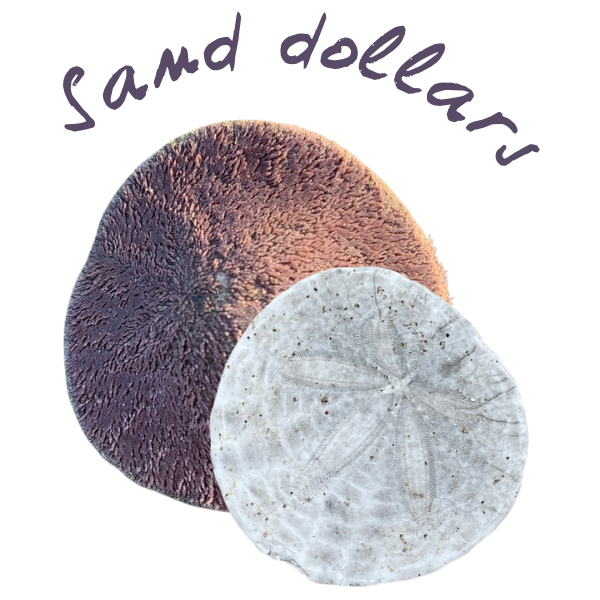

Free-floating sand dollar babies

The fate of the next generation? Pacific sand dollars leave it up to the currents.

From July to August, Pacific sand dollars (Dendraster excentricus) release sperm and eggs into the water column above them. This reproductive strategy, known as broadcast spawning, ensures that the eggs will not be eaten by hungry predators foraging on the sea floor. Coated by a protective jelly, the eggs free-float for about two weeks—at this stage, they’re termed what we think is the cutest juvenile wildlife name of all time: a pluteus. Eventually, the babies settle into the sand to continue growing, carrying sand as an anchor to prevent being swept away during strong currents.

Walking along Point Reyes’ beaches, you might come across a bleached sand dollar—different from its fuzzy, dark-colored appearance when it is alive in colonies beneath the water.

Naked Ladies

This August, clusters of tall, pink flowers are sprouting around the Seashore; the naked ladies’ (Amaryllis belladonna) maroon, leafless stems almost make them appear artificial, as if they’ve been pulled straight from the shelves of a craft store.

Early in the spring, their bright green leaves sprout up, gathering energy for the plant’s growth. Later in the year, the leaves die back, giving way to a striking bare stem—which has earned the plants their promiscuous name. In August and September, clusters of pink, trumpet-shaped flowers bloom; many associate their sudden appearance with the back-to-school season.

This flower is non-native—it was introduced from South Africa and has now become naturalized in California. Take a drive around the Seashore—you’ll likely see these beautiful ladies sprouting up along the roadside.

Skunkweed

This dainty purple flower has a…smelly…secret.

Point Reyes’ plant community monitoring team spotted (well…they smelled it first) some skunkweed (Navarretia squarrosa) while working in a grassland monitoring plot recently. When stepped on or brushed by an unsuspecting passerby, skunkweed’s pungent aroma fills the air. This native annual herb forms bright green mounds dotted with purple tubular flowers. Later in the flowering season, some of its sharp, pointy bracts turn red.

Point Reyes is part of the California Floristic Province, one of 36 internationally recognized biodiversity hotspots around the world where diversity of flora and fauna is most concentrated. Skunkweed is one of over 900 vascular plant species found at the Seashore—what are some of your favorite plants at Point Reyes?

Caspian Tern

Splash! With a coral red beak, black cap, and gray-white body, the caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia) dives headfirst into the water, catching a small silver fish for her chick.

This mother tern has her work cut out—her young hatched earlier this summer, and she fed them as they learned to fly within their first 30-35 days. But even after the young terns have learned to use their wings, the parents’ work isn’t over yet! Compared to other birds, caspian terns are known for their lengthy adolescence, remaining with their parents (and begging for food) for as long as eight months.

You might spot a caspian tern and its clingy adolescent along one of Point Reyes’ beaches.

Photo Credits: Skunkweed (header) – PRNSA; Caspian tern (header) – @coldbeer from Pexels; Townsend’s big-eared bat – NPS; Sand dollar (alive) – samberman via iNaturalist; Sand dollar (dried) – Robin Gwen Agarwal via iNaturalist; Naked ladies flowers – Maël Dewynter via iNaturalist; Skunkweed (in body text) – Karlyn H. Lewis vis iNaturalist; Caspian tern – Juan Bou Riquer