This month, the Seashore is flourishing—birds are busy building nests, babies are being born, and flowers are blooming! Explore some of Point Reyes’ April wonders below…and go out to experience the delights for yourself!

Throughout April:

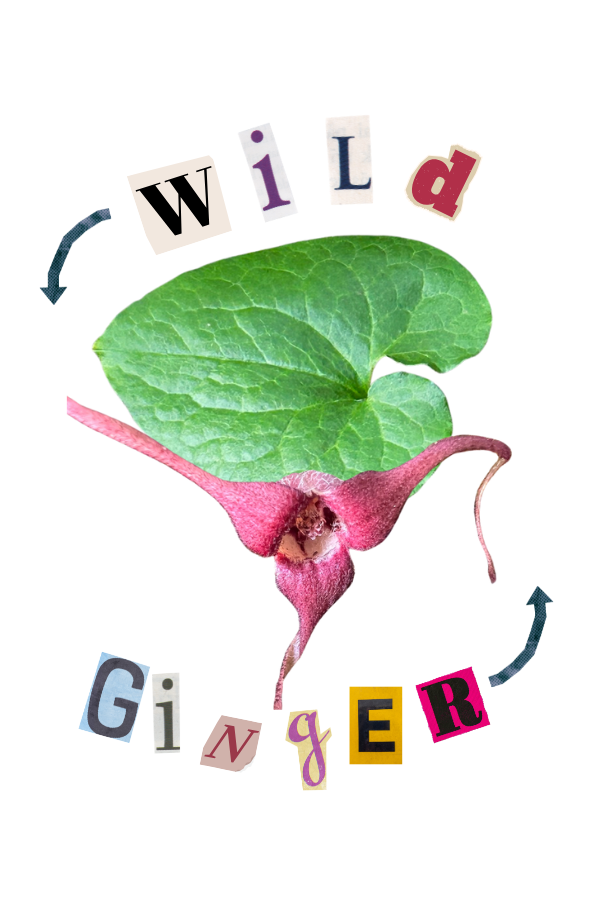

Western Wild Ginger

Point Reyes hikers often miss a spicy-scented forest floor wonder—the Western wild ginger (Asarum caudatum) flower. Though common in Point Reyes, the ginger’s big heart-shaped leaves are often mistaken for ivy and hide the elusive maroon-brown blooms growing beneath. Flowers appear from March to August, and contain seeds attached to peculiar worm-shaped appendages—which happen to be highly nutritious. Ants seeking a tasty meal claim these bundles, devouring only the lipid and protein-rich appendages and leaving behind the small seeds to grow a new generation of wild ginger plants.

Look out for wild ginger on moist, shaded trails, such as Bear Valley Trail. See if you can distinguish it from its ivy look-alike!

Throughout April:

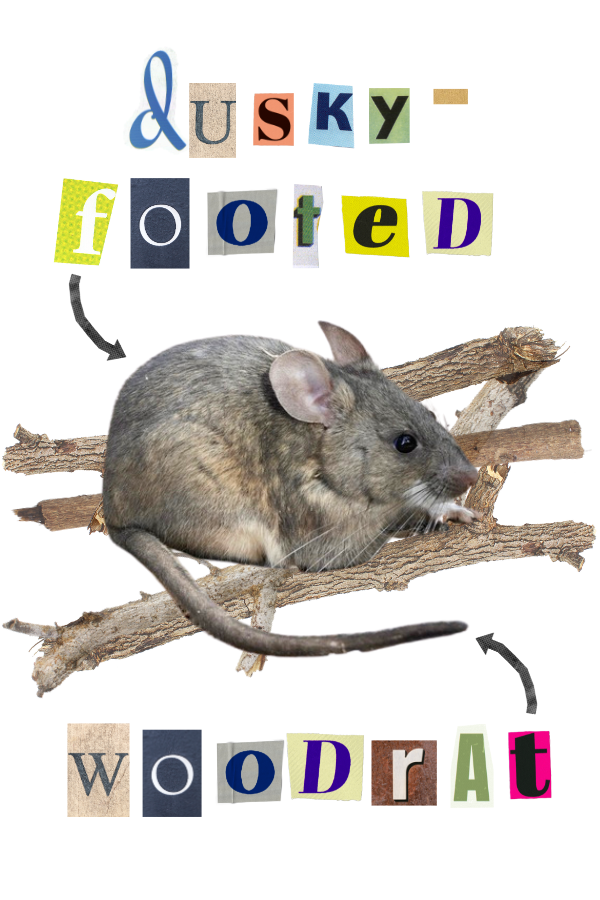

Castles of the Dusky-Footed Woodrats

Is that a pile of sticks and bark or….a dusky-footed woodrat castle? All over Point Reyes’ oak forests, dusky-footed woodrats (Neotoma fuscipes) are constructing grand castles of sticks—also known as “middens.”

Up to seven feet high and sometimes standing for over sixty years, woodrat nests are truly castles hidden in plain sight. The middens are complete with chambers of all kinds (including nurseries, pantries designated for specific fungi, leaves, and acorn foods, and outhouses) and are decorated with only the finest treasures—found bits of lace curtain, soap, gum wrappers, and even wallpaper. The rats line these chambers with nibbled bay laurel leaves, which release a potent oil that clears nests of pests such as mites, fleas, and ticks. Cleanliness in the castle is of the utmost importance to the woodrats; leaves are replaced every couple of days, and they regularly remove poop pellets from the outhouse to decompose outdoors.

Where there’s one castle, there’s often many more. When woodrats are ready to start their own families, they’ll often build their own midden or take over old nests (sometimes inhabited by our friend, the arboreal salamander); networks of grass trails link the homes in these multigenerational communities.

This April, dusky-footed woodrats are in the midst of their breeding seasons. You’ll likely spot some of their intricate castles in Point Reyes’ oak woodlands, such as along Bayview Trail.

Throughout April:

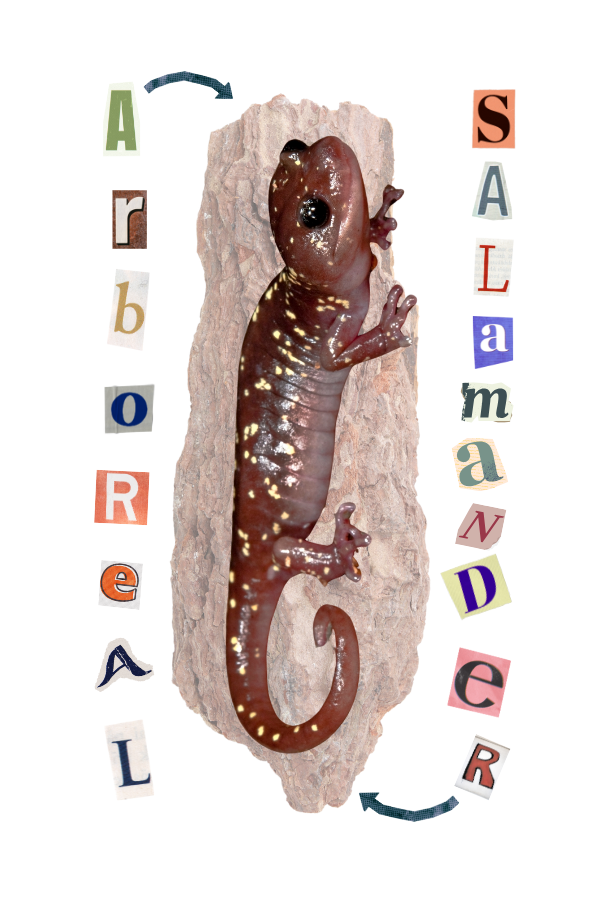

Skydiving Salamanders

High up in the moist crook of an oak tree, a dark, bulging eye shifts in search of passing prey. As a small moth flits by, a tongue projects, powerful jaws lock, and sharp teeth crunch. Legs climb further up the tree, toes grasp mossy contours of bark, and a brown tail curls around small branches. This creature is the arboreal salamander (Aneides lugubris)—Point Reyes’ tree-dwelling amphibian.

Suddenly, the salamander leaps away from the tree—a seemingly fatal decision for the small, wingless creature. Like a fearless skydiver, however, it spreads its long limbs out wide, slowing its speed and allowing for a more controlled descent to the forest floor. Researchers found that the salamanders can even maneuver in the air to change their landing location. As it turns out, the canopy-dweller’s unique features—long limbs and digits, as well as large feet—aid in climbing trees and are also critical for their safe descent. Check out the videos of an arboreal salamander jumping and flying, as recorded in the lab by salamander scientist, Dr. Christian Brown at the University of South Florida.

“Dropping, falling in a controlled way, even gliding at steep angles could all be evolutionary tactics to survive avian predation,” says Brown.

To keep their skin moist, arboreal salamanders tend to be most active during times of high moisture—during the rainy season and just after it. During April rains, look out for arboreal salamanders in Point Reyes’ oak woodlands, such as on Rift Zone Trail. Unless you are relocating them from harm, be sure not to touch them—their skin is absorbent and sensitive to oils, salts, and lotions on our hands.

Throughout April:

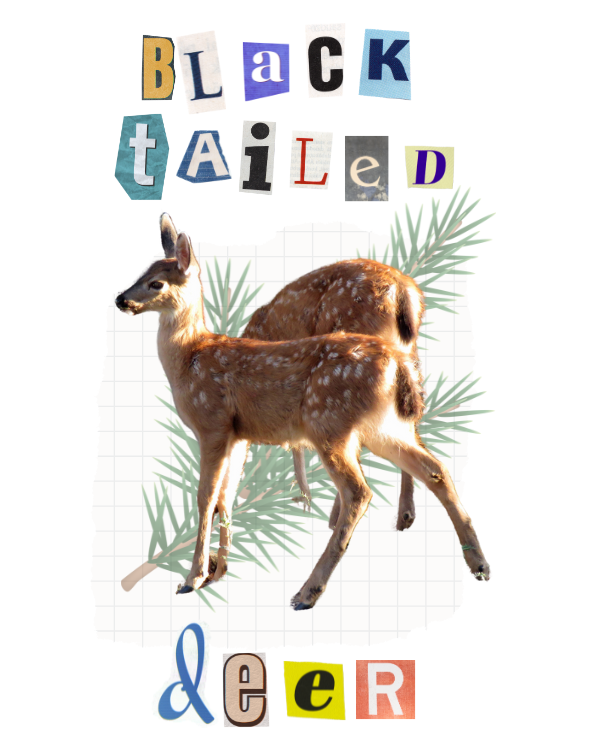

Hidden Babies

It’s baby season, and black-tailed deer fawns are being born! Weighing only about six pounds at birth, the delicate young have some tricks to survive in the big world. White spots help break up the fawns’ outlines and blend in with surroundings, and they have no scent for about a week after birth. Mothers hide their babies in bushes and long grasses to protect them from predators while they feed closeby. Welcome, little ones!

You’ll likely see black-tailed deer mothers and fawns all over the Seashore. If you come across a lone fawn, it is likely not abandoned and was purposefully hidden there by its mother. Nearby mothers may not return to their babies if people are too close by, so be sure to keep your distance. If the fawn is in a location where others may readily find it, feel free to report the location to a park employee—they will assess and cordon off the area if needed.

Throughout April:

An Osprey’s World

An osprey glides across Tomales Bay, a long piece of lichen hanging from its sharp talons. It delivers the material to its partner osprey, who expertly weaves the strand into the collection of branches, grasses, lichen, and bark laced together atop a dead tree. Year after year, the pair have returned to this very nest—refurbishing it, incubating eggs, raising their young. On the nest, they’ve braved winds and rains, watched the temperament of the tides, seen shooting stars and sleepy sunrises. They’ve experienced loss—bald eagles snatching their chicks—and joy—watching their fledglings spread their wings. Together, they’ve feasted on many herring, combed through their white feathers, and chased away overly nosy ravens. Each breeding season, the nest, the sweeping bay, and their chicks are the pair’s whole world—an osprey’s world.

This April, osprey are busy building nests around the Seashore before laying their eggs around the end of the month. Keep an eye out for their nests atop dead standing trees near water bodies and listen for their distinct high-pitched calls!

Credits for photos used in collages: arboreal salamander: rick734 / Canva; black-tailed deer – vince929 / iNaturalist; wild ginger flower – Amy Ruegg / iNaturalist; dusky-footed woodrat: TK Pham / iNaturalist; osprey – Skylar Ewing