From the sight of gray whales’ migration of hearts to the sound of elfin saddle mushrooms catapulting their spores up into the fresh forest air, Point Reyes is pulsing with life this new year. Welcome to January in Point Reyes!

Throughout January:

Pacific Gray Whales’ Migration of Hearts

Scanning the Pacific from the Point Reyes coast, you may spot heart-shaped mist rising from the deep blue—a watery sign of a gray whale’s (Eschrichtius robustus) deep exhale. Their uniquely shaped spouts are the result of the whales exhaling water vapor from the two blowholes at the top of their head (rather than one). This adaptation allows them to breathe quickly and efficiently during their 5,000-7,000 mile migration towards the warm lagoons of Mexico’s baja peninsula, where the whales give birth, mate, and nurse their newborns. The southbound stream of hearts occurs from December to February, with the most whales passing by Point Reyes in January.

Venture to a high coastal area—such as the Point Reyes Lighthouse, Chimney Rock Trail, or Tomales Point Trail—and keep an eye out for heart-shaped spouts, which are in contrast with the humpback whale’s tall, straight spout. Spouts are most visible on calm days with limited wind.

Throughout January:

The Sound of a Mushroom

While hiking through a pine forest in Point Reyes, you spot a black, wrinkled specimen sprouting amongst fallen needles, seemingly burnt or dried up. The elfin saddle (Helvella vespertina) is very much alive…you can even hear them. Many mature mushrooms drop their spores beneath them, hoping that wind or water will disperse the cells to new territory. Elfin saddles, on the other hand, confront this dispersal challenge with might—they catapult white spores from their caps, creating often audible “hissing” noises. The spores break past the “boundary layer” of calm air close to the ground, and up into a more turbulent airspace, where they can fly to fresh locales.

Keep an eye out for the elfin saddle on hikes through Point Reyes conifer forests, such as Bucklin Trail or Inverness Ridge…you might be lucky to hear one releasing its spores into the world.

Throughout January:

Coho Salmon Spawning

January is the peak spawning season for the coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) who migrate from the deep Pacific and up into waterways which run through Point Reyes, such as Lagunitas Creek. Here, they lay and fertilize thousands of tiny orange-red eggs in the riverbed. In fact, the streams in which the coho lay their eggs are the very same natal grounds where they were born about three years ago—and where they will die. The adults’ carcasses, filled with valuable nutrients gathered during their time at sea, help to nourish the surrounding forest ecosystem. This healthy forest, in turn, will help protect and support the young fish as they grow—and continue their incredible cycle of life.

This month, catch a glimpse of salmon and steelhead trout spawning in Lagunitas Creek—check out the Point Reyes National Seashore site for specific locations.

Throughout January:

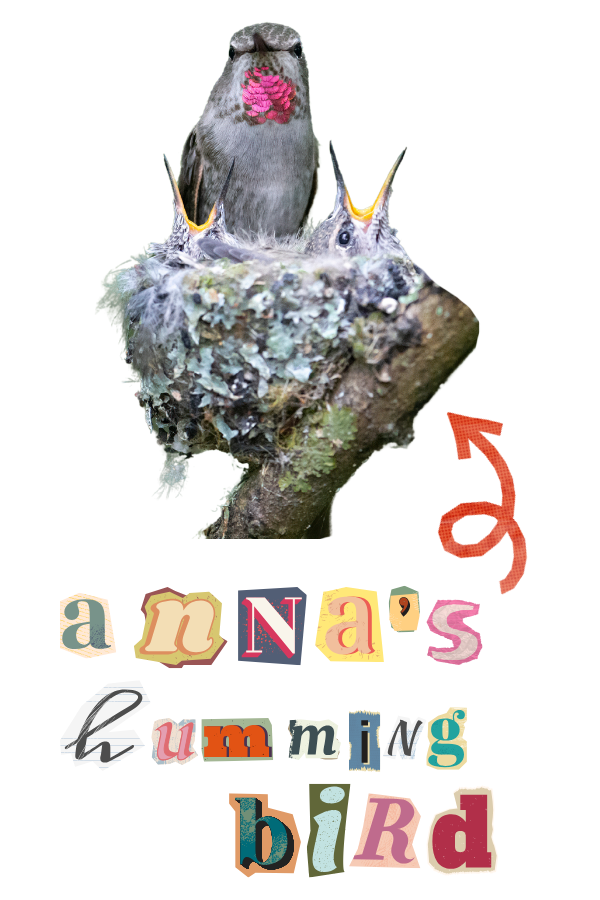

The Wintertime Busybodies

The midwinter slumber? The cold season slow-down? A winter’s rest? Of this, the Anna’s hummingbird knows not.

While some birds spend their cold January days roosting in Point Reyes (or overwintering in warmer locations), the Anna’s hummingbird (Calypte anna) is hard at work collecting soft spiderwebs, feathers, moss, lichen and grass to weave incognito cup-shaped nests. Here, these busybodies lay two pure white eggs which could hatch, grow, and fledge as early as late January—months before most other birds even begin their breeding season. In the early 1900s, these birds nested exclusively in northern Baja California and southern California—only in the last half of the century did they expand their range, likely due to more nectar feeders and exotic trees popping up in Northern California backyards.

It’s easy to sight Anna’s hummingbirds in many places in the Seashore, from oak woodlands to coastal scrub habitats. Look out for the male’s daring courtship dives!

Starting in January:

New Year, New Antlers

It’s the new year, and the male tule elk (Cervus canadensis nannodes) are ready to don a fresh look and discard old baggage. Some will begin shedding their antlers this month, which they’ve grown over the course of the year. No longer needed for dramatic displays of dominance (that drama needn’t be carried into 2025), the antlers serve a new purpose: nourishing the ecosystem. The bone is rich in minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, copper, and selenium; rodents and other small mammals chew on the antlers to file down their fast-growing teeth, and subsequently redispurse these valuable nutrients into the coastal ecosystem.

Tule elk are often grazing at Tomales Point or along the road to Drakes Beach. See this webpage to learn how to view elk safely and successfully.

Photos used in collages are from Getty Images, except for: elfin saddle – Avani Fachon and tule elk – NPS.