Wading Through Coastal Grasslands, California’s Quilted Refuge

July 21, 2025 | Words by Avani Fachon | Illustrations by Sophie Wood Brinker

This article is part one of Inflorescence, a series exploring the biodiversity of Point Reyes’ coastal grasslands and what land stewards are doing to preserve and restore this endangered habitat.

In·flo·res·cence: noun. 1. A cluster or arrangement of flowers which tops wildflowers and grasses. Visible if you bend to look closely in a Point Reyes coastal prairie, perhaps on a warm day. Some inflorescences contain a few flowers, and others—thousands. 2. Within the flowers are structures carefully shaped over time in response to other grassland kin1. 3. And further within those petals, anthers, lemma, and stamen, are strands of DNA—linked together by nucleotides of time, memory, and an irrepressible drive to propel forward. 4. Even if we forget to look closer, these molecules remember the story of their quilted refuge.

It’s an early summer afternoon in Point Reyes, and Kelsey Songer—botanist at Point Reyes National Seashore Association (PRNSA)—wades through a vast ocean of green. Waves of wind shake the grass and an alligator lizard scampers at her feet. Arriving at her destination, Songer outlines a small one-square-meter patch—a seemingly insignificant space in this vast landscape, like a single grain of sand on a beach. Within the patch sprouts a collection of grasses and low-growing plants which to an untrained eye….don’t seem like much.

But as an expert, Songer sees that this small corner of the grassland is a biodiversity hotspot , teeming with life. Using a hand lens, she begins identifying and counting each plant in the patch, noting each species and its abundance on a data sheet. She’s collecting this information as part of a National Park Service (NPS) initiative to build a long-term dataset on plant communities in Point Reyes and other Bay Area national parks. Her notes fill with names of grasses and herbaceous plants, from purple needlegrass and oatgrass to California buttercups and poppies.

The plot, as it turns out, is a patchwork quilt of diverse life.

“In a healthy grassland…upwards of 20 or 30 species are [found] within one quadrat,” says Songer, referencing the one-meter by one-meter patch that she outlined. “There can be a lot going on.” Songer moves to two nearby plots, carefully identifying more species—tufted hair grass, yarrow, western morning glory, and soap plant. “Within a site, even going from quadrat to quadrat can be super different—and that’s within a tiny area. So if you’re going from one grassland site to another, the species diversity can be wildly different.”

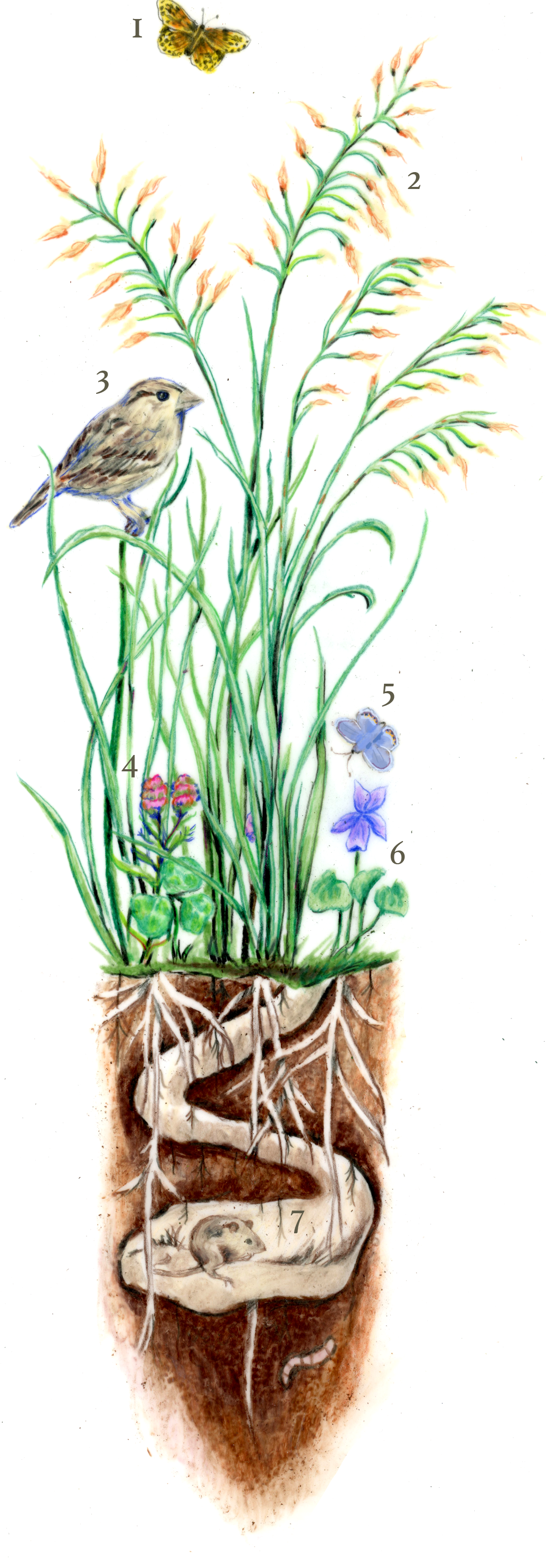

Songer is working in coastal prairie habitat—the most species-rich grassland type in North America, and a safe haven for over 90% of California’s rare plant species and 30% of the state’s threatened and endangered wildlife species. Coastal prairies in Point Reyes are a refuge to over 30 state-protected rare plants, from the dainty San Francisco owl’s clover to the spiky California bottlebrush grass. The endemic Point Reyes jumping mouse and several state-listed birds—such as the grasshopper sparrow and tricolored blackbird—nest and forage amongst a mosaic of grasses and wildflowers. California voles scurry along the grassland highways which connect their network of underground burrows. And notably, endangered Myrtle’s silverspots, golden-brown butterflies with an intricate black wing pattern, rest on western dog violet flowers. They’re the butterflies’ sole host plant and they thrive only in healthy coastal grasslands.

Songer understands why these highly diverse ecosystems are often underappreciated. “Say you’re coming to the Bay Area for the first time and you had the option of seeing grasslands or redwood forest. The redwood forest is an immersive experience with these massive, ancient marvels that are relatively easy to interact with. Grasslands exist at your feet; their complexity is easy to overlook and harder to connect with. But once you start to look, there’s so much going on,” she notes.

Beneath their already diverse above-ground world, grassland ecosystems are also vibrant underground. Native coastal prairie plants, such as bunchgrasses, often develop extensive root systems meant to help them stay resilient during dry summertime conditions. These roots stabilize soil and serve as storage banks for carbon—contributing to the estimated one third of global terrestrial carbon stocks which grasslands stow away. Researchers have found that grasslands are a more reliable carbon sink than trees in the face of climate change, as they better tolerate drought and wildfire; carbon accumulated in their root systems remains underground after a fire, rather than being released into the atmosphere. Microbial communities establish symbioses with these deep, resilient roots, enhancing the soil’s fertility. Both above and below ground, coastal prairies are pulsing with life—contrary to the popular misconception that grasslands are comparable to a single-species lawn.

“Grasslands aren’t your lawn in the same way that an ocean is not a swimming pool,” says Dylan Voeller, NPS range program manager at Point Reyes. “These are complex ecosystems with unique assemblages and histories tied to place.” Through his work to ensure sustainable use of the park’s rangelands, Voeller—like Songer—is a regular witness to the richness of grassland ecosystems. While out doing fieldwork, he looks across the quilted landscape, admiring the clusters of California brome dancing amongst vining morning glory.

The Shifting Baseline

Growing up in Los Angeles County, Voeller caught glimpses of wildflowers and bunchgrasses sprouting in empty lots between buildings. But in the most populous county in the United States, such sightings were scarce; many spaces which used to be grasslands and dunes were developed into malls, neighborhoods, parking lots, and oil fields. When Voeller made his way to Point Reyes National Seashore, he was struck by the park’s large swaths of coastal prairie. “Point Reyes is a model of less developed landscapes which I would find little snippets of in Southern California,” explains Voeller.

The data that Songer and Voeller are collecting is becoming increasingly valuable as healthy coastal prairies become a rarity across California. Many of these landscapes—along with the fauna that live there—are being lost and forgotten. As one of California’s most rapidly vanishing ecosystems, less than 1% of the prairies’ historical extent remains intact across the state—a portion of which is housed at Point Reyes National Seashore. Over time, this ecosystem across other parts of California has largely been overrun by invasive species or replaced with cities and farms. As it vanishes, we are in peril of not only losing its function and beauty, but forgetting it ever existed at all, a sort of generational amnesia.

“I wish people could love grasslands as much as I do,” says Eric Wrubel, biologist at Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Wrubel collaborates with Songer and Voeller on initiatives to better understand and support grasslands, and leads several successful grassland restoration projects at Sweeney Ridge and Montara Prairie. For millennia, these grasslands—and prairies across California—were carefully tended by native peoples, who weeded, pruned, and harvested the land, as well as used fire to regenerate the ecosystem. With the cultural suppression of fire and other Indigenous land management practices, Sweeney Ridge and Montara Prairie were heavily reshaped by shrubs and trees, creating an environment unsuitable for the many native plants which rely upon grassland environments to thrive. Wrubel and a restoration team reached back into the memory of the landscape’s story, and worked to steward the lands into a flourishing, grassy prairie.

However, this story of remembrance is not common in our fast-moving world. “Have you heard of the shifting baseline syndrome?” asks Wrubel. “You don’t know what you’ve lost when it’s not there anymore. There’s not a lot of memory of what California used to look like or be like.”

Through their work with grasslands, Voeller, Songer, and Wrubel all have the same vision—to sustain and restore the eco-memory of California’s unsung refuge, whose mosaic of beauty and resilience comes from layers of patchwork—of species and of history through generations.

“Sometimes when I’m in a coastal grassland, I just feel connected to something so much bigger than myself,” says Wrubel. “Your senses are alive. You can feel the breeze on your face and see the ocean and lie down in the grass and look at the bees flying by.” And so it feels, to be part of this grand quilt woven together by common threads—strings of resolve for memory and resilience.